18 Definition

Highlights of this Chapter: We define infinite series and infinite products, and relate them through via exponential functions and logarithms, reducing the theory to the study of one or the other. We then introduce two classes of series that we can essentially compute by hand: telescoping sums, and the geometric series.

We return from our excursion into the study of functions back to sequences for a short bit, and discuss two particular types of recursive sequences which prove to be extremely useful across mathematics: infinite series, and infinite products. Most of the material in this section and the following could easily have been covered much earlier - the reason we have postponed them is that the most striking applications of sequences and series involve not numbers but whole functions, and now that we have that technology available we will be able to present the theory in its fullest.

Definition 18.1 (Series) A series \(s_n\) is a recursive sequence defined in terms of another sequence \(a_n\) by the recurrence relation \(s_{n+1}=s_n+a_n\). Thus, the first terms of a series are \[s_0=a_0,\hspace{1cm}s_1+a_0+a_1\hspace{1cm}s_2=a_0+a_1+a_2\ldots\] We use summation notation to denote the terms of a series: \[s_n=_0+a_1+\cdots+a_n=\sum_{k=0}^na_k\]

Remark 18.1. It is important to carefully distinguish between the sequence \(a_n\) of terms being added up, and the sequence \(s_n\) of partial sums.

When a series converges, we often denote its limit using summation notation as well. The traditional ‘calculus notation’ sets \(n\) to infinity as the upper index; and another common notation is to list just the subset of integers over which we sum in as the lower bound: all of the following are acceptable

\[\lim s_n = \lim \sum_{k=0}^n a_k = \sum_{k=0}^\infty a_k=\sum_{k\geq 0}a_k\]

There are many important infinite series in mathematics: one that we encountered earlier is the Basel series first summed by Euler. \[\sum_{n\geq 1}\frac{1}{n^2}=\frac{\pi^2}{6}\]

When the sequences \(a_n\) consists of functions of \(x\), we may define an infinite series function for each \(x\) at which it converges. These describe some of the most important functions in mathematics, such as the Riemann zeta function \[\zeta(s)=\sum_{n\geq 1}\frac{1}{n^s}\]

One of our big accomplishments to come in this class is to prove that exponential functions can be computed via infinite series, and in particular, the standard exponential of base \(e\) has a very simple expression

\[\exp(x)=\sum_{n\geq 0}\frac{x^n}{n!}\]

Remark 18.2. Because the sum of any finitely many terms of a series is a finite number, we can remove any finite collection without changing whether or not the series converges. In particular, when proving convergence we are free to ignore the first finitely many terms when convenient.

Because of this, we often will just write \(\sum a_n\) when discussing a series, without giving any lower summation bound.

The other infinite algebraic expression we can conjure up is infinite products:

Definition 18.2 (Infinite Products) An infinite product \(p_n\) is a recursive sequence defined in terms of another sequence \(a_n\) by the recurrence relation \(p_{n+1}=p_na_n\). Thus, the first terms of a series are \[s_0=a_0,\hspace{1cm}s_1+a_0a_1\hspace{1cm}s_2=a_0a_1a_2\ldots\] We use product notation to denote the terms of a series:_ \[s_n=_0a_1\cdots a_n=\prod_{k=0}^na_k\]

Again, like for series, when such a sequence converges there are multiple common ways to write its limit:

\[\lim p_n = \lim \prod_{k=0}^n p_k = \prod_{k=0}^\infty p_k =\prod_{k\geq 0}p_k\]

The first infinite product to occur in the mathematics literature is Viete’s Product for \(\pi\)

\[\frac{2}{\pi}=\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\frac{\sqrt{2+\sqrt{2}}}{2}\cdots\]

This product is derived from Archimedes’ side-doubling procedure for the areas of circumscribed \(n\)-gons; hence the collections of nested roots!

Another early and famous example being Wallis’ infinite product for \(2/\pi\), which instead is derived from Euler’s infinite product for the sine function.

\[\frac{\pi}{2}=\prod_{n\geq 1}\frac{4n^2}{4n^2-1}\] \[=\frac{2}{1}\frac{2}{3}\frac{4}{3}\frac{4}{5}\frac{6}{5}\frac{6}{7}\frac{8}{7}\frac{8}{9}\frac{10}{9}\frac{10}{11}\frac{12}{11}\frac{12}{13}\frac{14}{13}\frac{14}{15}\cdots\]

In 1976, the computer scientist N. Pippenger discovered a modification of Wallis’ product which converges to \(e\):

\[\frac{e}{2}=\left(\frac{2}{1}\right)^{\frac{1}{2}}\left(\frac{2}{3}\frac{4}{3}\right)^{\frac{1}{4}}\left(\frac{4}{5}\frac{6}{5}\frac{6}{7}\frac{8}{7}\right)^{\frac{1}{8}}\left(\frac{8}{9}\frac{10}{9}\frac{10}{11}\frac{12}{11}\frac{12}{13}\frac{14}{13}\frac{14}{15}\frac{16}{15}\right)^{\frac{1}{16}}\cdots\]

Pippenger wrote up his result as a paper…but due to the relatively ancient tradition of mathematics he was adding to - he decided to write it in Latin! The paper appears as “Formula nova pro numero cujus logarithmus hyperbolicus unitas est”. in IBM Research Report RC 6217. I am still trying to track down a copy of this! So if any of you are better at the internet than me, I would be very grateful if you could locate it.

Alluded to above, one of the most famous functions described by an infinite product is the sine function, which Euler expanded in his proof of the Basel sum \[\frac{\sin \pi x}{\pi x}=\prod_{n\geq 1}\left(1-\frac{x^2}{n^2}\right)\]

AAs well as our friend the Riemann zeta function from above, which can be written as a product over all the primes! (Alluding to its deep connection to number theory)

\[\zeta(s)=\prod_{p\,\mathrm{prime}}\frac{1}{1-p^{-s}}\]

Perhaps in a calculus class you remember seeing many formulas for the convergence of series (we will prove them here in short order), but did not see many infinite products. The reason for this is that it is enough to study one class of these recursive sequences, once we really understand exponential functions and logarithms: we can use these to convert between the two.

Proposition 18.1 (Relating Products to Series) Let \(p_n=\prod_{k=0}^n a_k\) be a product, and \(L\) a logarithm function. Then \(p_n\) converges if and only if the series \(s_n=\sum_{k=0}^n L(a_k)\) converges.

Furthermore, if we can explicitly sum the series \(s_n\to s\) then \(p_n\to E(s)\), where \(E\) is an exponential with the same base as \(L\).

Proof. Let \(p_n\) be a convergent product, so \(p_n\to p\) and \(L\) a logarithm. Then since \(L\) is continuous, we know \(L(p_n)\to L(p)\). But each term \(p_n\) is a finite product so inductively using the law of logarithms yields \[\begin{align*}L(p_n)&=L(p_0p_1p_2\cdots p_n) \\ &=L(p_0)+L(p_1)+L(p_2)+\cdots+L(p_n) \\ &= \sum_{k=0}^n L(p_k) \end{align*}\]

Thus, \(\sum L(p_k)\) converges, as claimed. Now for the reverse, let \(E\) be the exponential function whose base is the same as \(L\) and assume that \(s_n\sum L(p_k)\to s\) converges. Since \(E\) is continuous, we see that \(E(s_n)\) is convergent. Using the law of exponents on each finite term shows \[\begin{align*} E(s_n)&=E\left(L(p_0)+L(p_1)+\ldots L(p_n)\right)\\ &=\prod_{k=0}^n E(L(p_k))\\ &=\prod_{k=0}^n p_k \end{align*}\]

Thus \(p_k\) converges, to \(E(s)\).

This is yet another reason that we should desire a rigorous theory of the transcendental functions, as the ability to turn multiplication into addition is useful in theory, just as it was in practice centuries ago.

In this chapter we begin our study of series by looking at some common types of series, and how to check if these converge or diverge. In the following chapters we will develop more powerful convergence tests, and use them to study series of functions, as well as series of numbers.

18.1 Telescoping

Definition 18.3 (Telescoping Series) A telescoping series is a series \(\sum a_n\) where the terms themselves can be written as differences of consecutive terms of another sequence, for example if \(a_n=t_n-t_{n-1}\).

Telescoping series are the epitome of a math problem that looks difficult, but is secretly easy. Once you can express the terms as differences, everything but the first and last cancels out! For example:

Once a series has been identified as telescoping, often proving its convergence is straightforward: you get a direct formula for the partial sums, and then all that remains is to calculate the limit of a sequence.

Example 18.1 The sum \(\sum_{k\geq 1}\frac{1}{k}-\frac{1}{k+1}\) telescopes. Writing out a partial sum \(s_n\), everything collapses so \(s_n=1-\frac{1}{n+1}\).

Now we no longer have a series to deal with, as we’ve found the partial sums! All that remains is the sequence \(s_n=1-\tfrac{1}{n+1}\). And this limit can be computed immediately from the limit laws:

\[s = \lim s_n = 1-\lim \frac{1}{n+1}=1\]

Of course, sometimes a bit of algebra needs to be done to reveal that a series is telescoping:

Exercise 18.1 Show that the following series is telescoping, and then find its sum \[\sum_{n\geq 1}\frac{4}{n^2+n}\] Hint: factor the denominator, and do a partial fractions decomposition!

A telescoping product is defined analogously

Definition 18.4 (Telescoping Product) A telescoping product is a product \(\prod a_n\) where the terms themselves can be written as ratios of consecutive terms of another sequence, for example \(a_n=\frac{t_n}{t_{n-1}}\).

Exercise 18.2 Prove that if \(p_n\) is a telescoping product, then \(s_n=L(p_n)\) is a telescoping series.

18.2 Geometric Series

Definition 18.5 A series \(\sum a_n\) is geometric if all consecutive terms share a common ratio: that is, there is some \(r\in\RR\) with \(a_n/a_{n-1}=r\) for all \(n\).

In this case we can see inductively that the terms of the series are all of the form \(ar^n\). Thus, often we factor out the \(a\) and consider just series like \(\sum r^n\).

Exercise 18.3 (Geometric Partial Sums) For any real \(r\), the partial sum of the geometric series is: \[1+r+r^2+\cdots+r^{n}=\sum_{k=0}^n r^n=\frac{1-r^{n+1}}{1-r}\]

Like telescoping series, now that we have explicitly computed the partial sums, we can find the exact value by just taking a limit.

Theorem 18.1 If \(|r|<1\) then \(\sum r^n\) converges, and \[\sum_{k=0}^\infty r^k=\frac{1}{1-r}\]

Proof. By the partial sum formula, we have

\[\sum_{n\geq 0}r^n=\lim \sum_{k=0}^n r^n=\lim \frac{1-r^{n+1}}{1-r}\] Since \(|r|<1\), we know that \(r^n\to 0\), and so \(r^{n+1}=rr^n\to 0\) by the limit theorems (or by truncating the first term of the sequence). Again by the limit theorems, we may then calculate \[\lim \frac{1-r^{n+1}{1-r}}=\frac{1-\lim r^{n+1}}{1-r}=\frac{1-0}{1-r}=\frac{1}{1-r}\]

Remark 18.3. Its often useful to commit to memory the formula also for when the sum starts at \(1\): \[\sum_{k=1}^\infty r^k=\frac{r}{1-r}\]

Exercise 18.4 Prove that for all \(|r|\geq 1\), the geometric series \(\sum r^n\) diverges. Hint: use the formula for the partial sums and the limit theorems, which reduces this to the study of the sequence \(r^{n+1}\).

Because this holds for all values of \(r\) between \(-1\) and \(1\), this gives us our first taste of a function defined as an infinite series. For any \(x\in (-1,1)\) we may define the function \[f(x)=1+x+x^2+x^3+\cdots +x^n+\cdots\] and the argument above shows that \(f(x)=1/(1-x)\). Thus, we have two expressions of the same function: one in terms of an infinite sum, and one in terms of familiar algebraic operations. This sort of thing will prove extremely useful in the future, where switching between these two viewpoints can often help us overcome difficult problems. \[\frac{1}{1-x}=1+x+x^2+x^3+x^4+x^5+\cdots\]

18.2.1 Quadrature of the Parabola

We may now revisit Archimedes’ other famous argument - discovering the area of the parabola.

Theorem 18.2 The area of the segment bounded by a parabola and a chord is \(4/3^{rd}\)s the area of the largest inscribed triangle.

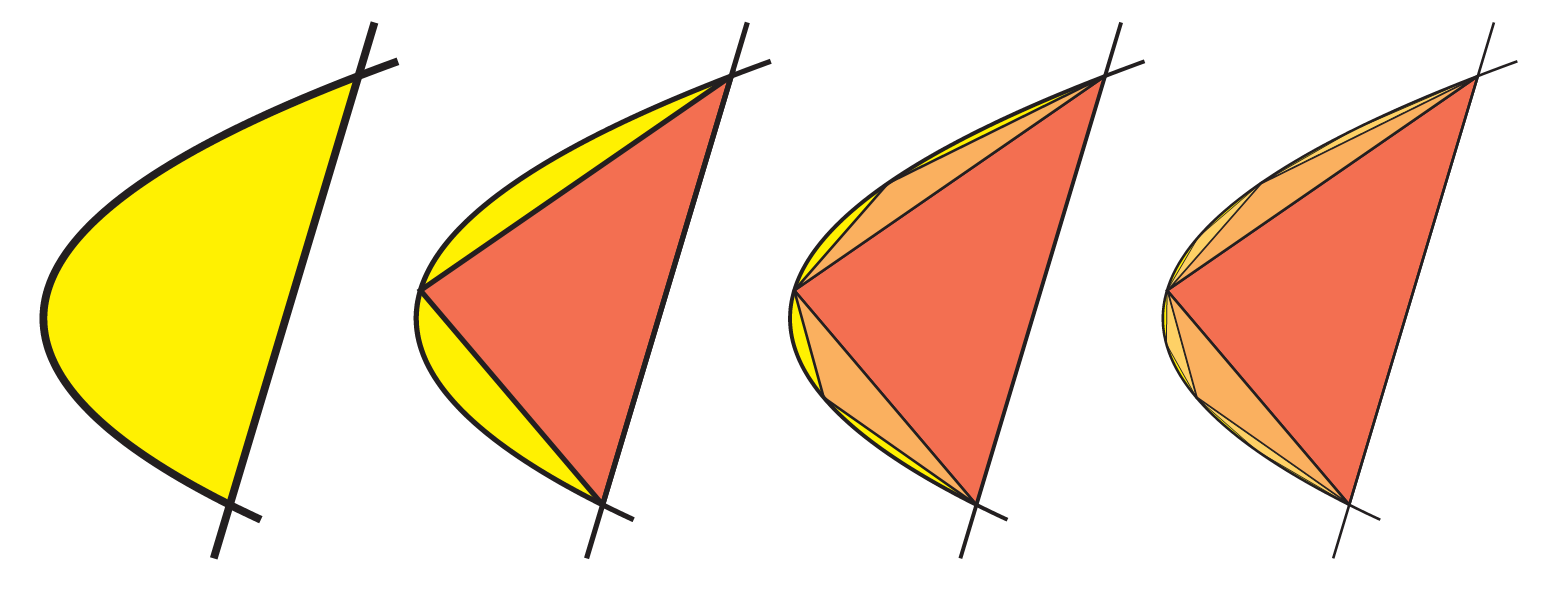

After first describing how to find the largest inscribed triangle (using a calculation of the tangent lines to a parabola), Archimedes notes that this triangle divides the remaining region into two more parabolic regions. And, he could fill these with their largest triangles as well!

These two triangles then divide the remaining region of the parabola into four new parabolic regions, each of which has their own largest triangle, and so on.

The key geometric step to Archimedes argument is to realize that the total area of triangles added at each stage is proportional to the area of triangles added at the previous stage:

Proposition 18.2 (Area of the \(n^{th}\) stage) The total area of the triangles in each stage is \(1/4\) the total area of triangles in the previous stage.

That is, if \(a_n\) is the area in the \(n^{th}\) stage, Archimedes is saying that \(a_{n+1}=\tfrac{1}{4}a_{n}\). From here, the calculation step of the argument can be made rigorous with the real analysis of infinite series.

Exercise 18.5 Archimedes has defined \(a_n\) as a recursive sequence above. Use this to get an explicit formula for \(a_n\) in terms of \(T\), the original area of the first triangle. Now, let \(A_n\) be the total area of the triangles up to the \(n^{th}\) stage. Show that this gives a geometric series, whose sum is \(4/3 T\).

There is a final part to this argument, that takes some more real-analysis work: since each of these triangles is a subset of the original parabola, the overall shape constructed from their union is also a subset, and so the area of the limit is less than or equal to the area of the parabola. But why is it equal? This requires us to show that area missed by each finite stage converges to zero.

Archimedes carefully works out the geometry to prove that this sequence of errors \(E_n\) must go to zero. Thus, as the area \(A_P\) of the parabola at each stage is \(A_P = A_n + E_n\), and since both \(A_n\) and \(E_n\) converge we can use the limit theorems:

\[A_P=\lim (A_n+E_n)=\lim A_n + \lim E_n = \frac{4}{3}T+ 0 = \frac{4}{3}T\]

Exercise 18.6 (Parabola Error (Challenge)) Try to sketch an argument for why \(E_n\) goes to zero. It’s hard to write down a formula directly, as this describes the area of a shape with a curved side, and if we knew how to do that we would have sovled the entire probelm directly!

Instead, can you prove that if \(p\) is any point inside the original parabola segment, that \(p\) must be contained in the \(n^{th}\) stage of triangles for some \(n\)? Then, since at some finite stage every point can be removed from \(E_n\), the limit of \(E_n\) is empty, which has area zero.

18.2.2 The Koch Fractal

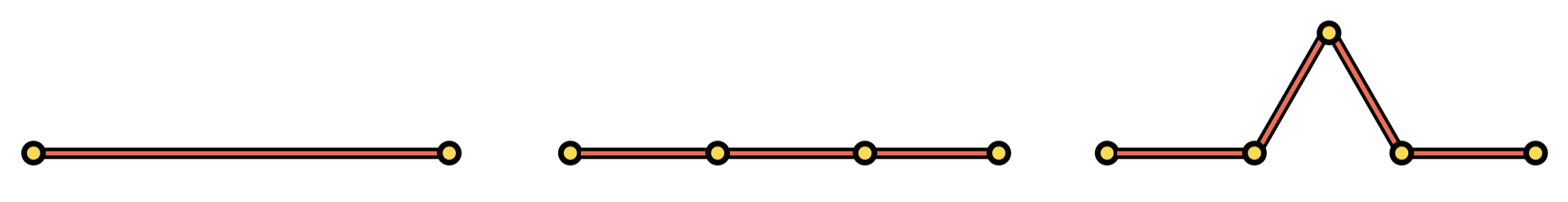

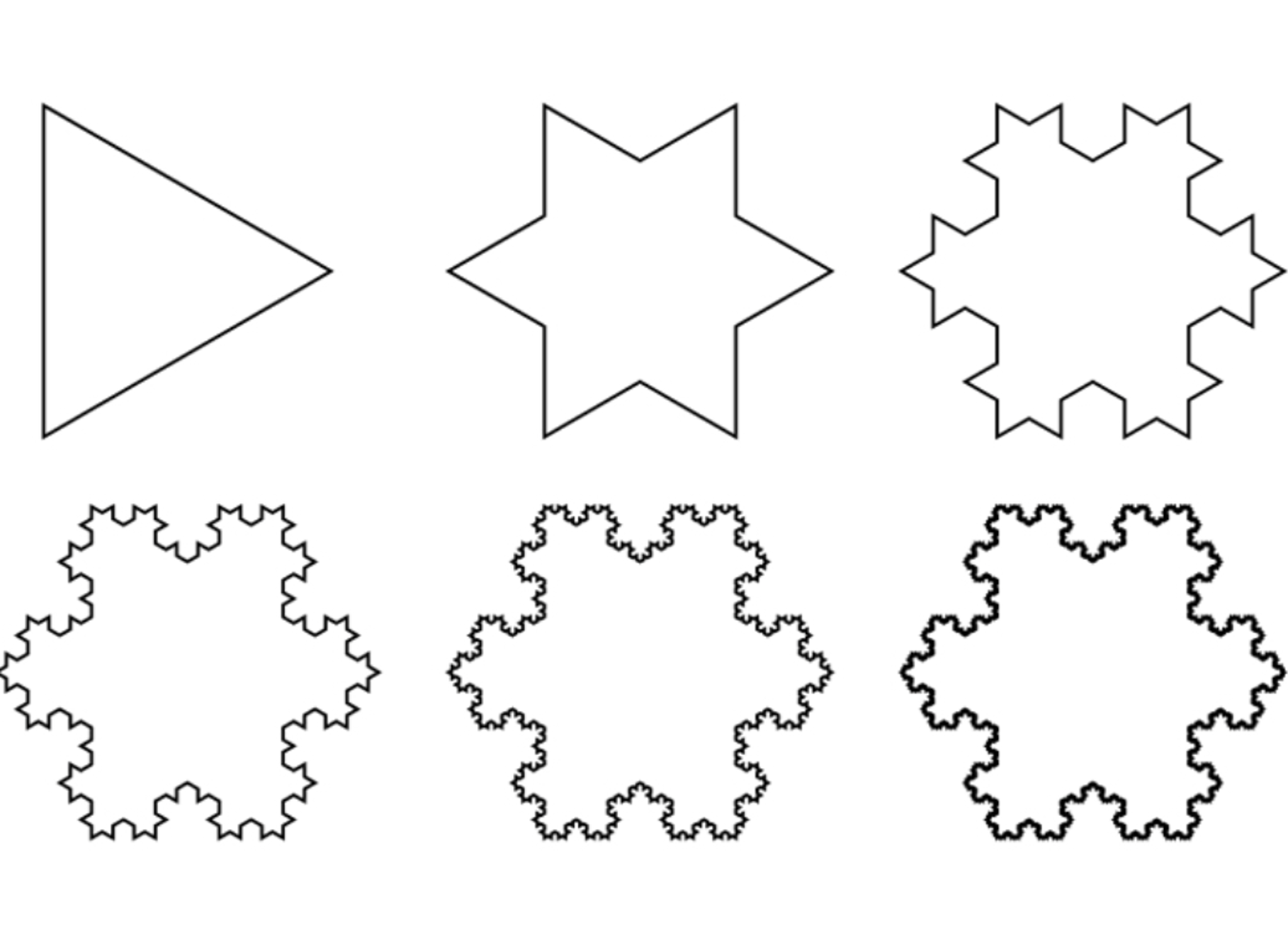

The Koch Snowflake is a fractal, defined as the limit of an infinite process starting from a single equilateral triangle. To go from one level to the next, every line segment of the previous level is divided into thirds, and the middle third replaced with the other two sides of an equilateral triangle built on that side.

Doing this to every line segment quickly turns the triangle into a spiky snowflake like shape, hence the name. Denote by \(K_n\) the result of the \(n^{th}\) level of this procedure.

Say the initial triangle at level \(0\) has perimeter \(P\), and area \(A\). Then we can define the numbers \(P_n\) to be the perimeter of the \(n^{th}\) level, and \(A_n\) to be the area of the \(n^{th}\) level..

Exercise 18.7 (The Koch Snowflake Length) What are the perimeters \(P_1,P_2\) and \(P_3\) of the first iterations? From this conjecture (and then prove by induction) a formula for the perimeter \(P_n\) and prove that \(P_n\) diverges. Thus, the limit cannot be assigned a length!

Next we turn to the area: recall that the area of an equilateral triangle can be given in terms of its side length as \(A=\sqrt{3}{2}s^2\)

Exercise 18.8 (The Koch Snowflake Area) What are the areas \(A_1,A_2\) and \(A_3\) in terms of the original area \(A\)? Find an infinite series that represents the area of the \(n^{th}\) stage \(A_n\), and prove that your formula is correct by induction.

Now, use what we know about geometric series to prove that this converges: in the limit, the Koch snowflake has a finite area even though its perimeter diverges!